Now we know what Christians, by definition, believe, we might think their beliefs to be quite extraordinary. But if Christians' beliefs were ordinary, there would be no Christianity: it is the recording of the exceptional throughout history that forms much of the bible.

Concerning the recording of that history, a question I have often heard is weren't people back then just less well educated and so more gullible?

, or in other words, isn't the eyewitness testimony in the bible therefore untrustworthy?

It is a good question, or at least I thought it was, because I found it to be a nagging question that I had often asked myself.

Reading around, trying to find an answer to that question, I realised that for the question to hold water, three suppositions must be true, namely: previous generations have always accepted religion; previous generations were unintelligent, or much less intelligent than our own; and the majority of people today are atheists.

A common phrase I've heard, often from people who should know better, is people used to have religion, but now we have science

, as if religion and science are fulfilling the same purpose, or that science never used to exist.

Despite the common misconception that religion has always been accepted, it is remarkably easy to discover that doubt in the supernatural has always been present, and, consequently, it is quite wrong to think religion has always been accepted.

In ancient Greece, athiests made objections against religion not on scientific grounds, but on the paradoxical nature of being asked to accept things that aren't intuitively there in the tangible world. In the fourth century BC, Plato imagines a believer in the Greek gods chastising an atheist: You and your friends are not the first to have held this view about the gods! There are always those who suffer from this illness, in greater or lesser numbers

. Plato's discussion clearly favours the theists, but the fact that he wrote this conversation demonstrates atheism was not uncommon.

There are many other examples of atheism is early history, such as Carneades, the head of the Platonic academy in the second century BC, who argued that belief in gods is illogical

, to the Epicureans of antiquity, who rejected the supernatural on principle and who were often called atheoi, and the atheistic writings of Xenophanes of Colophon, a prominent Greek thinker.

The belief that the supernatural does not exist has been present throughout history, not just infrequently held by a rare philosopher, but by philosophers, ordinary people and whole sects of people. Even amongst the Jewish people at the time of Jesus - who all believed in God and from where Christianity was born - one of the four main sects, the Sadducees, maintained there was no afterlife.

Most cultures in human history have had a form of supernatural belief, of one sort or other. But that's not to say that every person in every culture has subscribed to it. Since the dawn of religion, there has always been those that challenged it: religion has never been universally accepted, and rejecting it is nothing new. Religion has always been challenged, and Christianity was challenged vehemently and violently at its beginnings: even the theists, and even the Jews who would not accept Christianity, found the newly founded fifth Jewish sect, Christianity, to be intolerable: the idea of God dying on the cross went utterly against what they knew of God, and so was unacceptable to many. This is highlighted in a letter from St. Paul - one of the leaders of the Christian Church, who had previously been one of its most notorious persecutors - to the Christian Church in Corinth:

For the message of the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God...For since, in the wisdom of God, the world through wisdom did not know God, it pleased God through the foolishness of the message preached to save those who believe. For Jews request a sign, and Greeks seek after wisdom; but we preach Christ crucified, to the Jews a stumbling block and to the Greeks

foolishness

It is clear that religious belief has never been accepted unquestioningly, particularly new beliefs or new ideas within a religion. Nevertheless, belief in the supernatural has been the dominant belief throughout history.

Even though we see that religion has not always been accepted, and at times it has been outright rejected, we must understand whether those who did believe in God did so because they were dim-witted and gullible.

We have already heard how the Big Bang theory (Fr. Georges Lemaitre, 1927) and genetic inheritance (Gregor Mendel, 1866) were put forward by a priest and a monk, and as such, their contemporaries in their fields were Albert Einstein and Charles Darwin. Clearly, these members of previous generations were intelligent. However, it may still be argued that they were alive and working at the dawning of a scientific age, and consequently, had not yet thrown off religious thinking and embraced only science.

The advanced knowledge we enjoy today, and indeed the knowledge understood at the time of Einstein, Lemaitre, Darwin, Mendel and all previous generations, stands on the work from the greats of the previous generations, such as Isaac Newton (1643 - 1727), Leonardo Da Vinci (1452 - 1519) and Pythagoras (570 BC - 495 BC), to name a few of the most famous great minds from history. These well-known greats, and many others, lived hundreds to thousands of years ago. It is obvious that previous generations had their geniuses, and today's knowledge is a culmination of research and understanding leading back throughout history.

But, were these famous previous greats, and the many others we haven't mentioned, just a few shining lights in a sea of ignorance? Without the widespread knowledge we have today, were the masses more likely to ascribe inexplicable events to the supernatural?

As one might expect, much work has gone into understanding whether previous generations were indeed gullible. Much modern scholarship would disagree with that claim:

In antiquity miracles were not accepted without question. Graeco-Roman writers were often reluctant to ascribe

miraculous events to the gods, and offered alternative explanations. Some writers were openly skeptical about

miracles (e.g. Epicurus; Lucretius; Lucian). So it is a mistake to write off the miracles of Jesus as the result

of the naivety and gullibility of people in the ancient world.

In the relatively peaceful and stable period of the first two centuries the irrationalism which first appeared

at the beginning of the first century was unable to strike roots. There continued to be rationalist movements

alongside it. In his dialogues Lucian mocked his contemporaries' belief in the miraculous. Oenomaus of Gadara

mocked the oracles, and Sextus Empiricus once more brought together all the arguments of scepticism. Even where

increased irrationalism was notable it remained within bounds, without

eccentricity or fanaticism. There was no decisive change before the great social and political crisis of the 3rd

century AD.

Primitive Christian belief in the miraculous thus has a crucial role in the religious development of late

antiquity. It stands at the beginning of the 'new' irrationalism of that age. Our brief outline of this

development may have done something to correct the widespread picture of an ancient belief in the miraculous

which has no history. What we have found here is not a rampant jungle of ancient credulity with regard to

miracles, but a process of historical transformation in which forms and patterns of belief in the miraculous

succeed one another. If we accept this picture, we must firmly reject assertions that primitive Christian belief

in the miraculous represented nothing unusual in the context of its period.

It is in this light that we must judge the accounts we possess of other miracle-workers in Jesus' period and

culture. We have already observed that the list of such occurrences is very much shorter than is often supposed.

If we take the period of four hundred years stretching from two hundred years before to two hundred years after

the birth of Christ, the number of miracles recorded which are remotely comparable with those of Jesus is

astonishingly small. On the pagan side, there is little to report apart from the records of cures at healing

shrines, which were certainly quite frequent, but are a rather different phenomenon from cures performed by an

individual healer. Indeed it is significant that later Christian fathers, when seeking miracle workers with whom

to compare or contrast Jesus, had to have recourse to remote and by now almost legendary figures of the past

such as Pythagoras or Empedocles.

Even Jesus' closest disciples were reluctant to commit to an answer when Jesus asked them, who do people say I

am?

It was only Peter out of the twelve who first had the courage to call Jesus, Christ. The famous story of one of

Jesus' disciples, St. Thomas, not believing Jesus could have risen from the dead shows us that people were not

necessary gullible: even Thomas, who had seen Jesus' miracles first-hand, such as the healing and bringing back

to life of others, would not believe the other disciples when they told him Jesus had risen from the dead, until

he had seen Jesus with his own eyes.

So, we see that before Jesus' miracles there was little recorded belief in miracles: miracles were not commonplace and claims of miracles were not easily believed, particularly by those with the education to record them and the public standing to refute them.

I came to realise the modern view that all previous generations were credulous is wrong. In that view, I found myself in very good company: C.S. Lewis, a very bright and well-educated mind, put it into words far more eloquently than I ever could. C.S. Lewis' friend, Owen Barfield had converted to Anthroposophy and was seeking to get Lewis, an atheist at the time, to join him. One of Lewis's objections was that religion was simply outdated. It was an objection he later realised had been demolished:

Barfield never made me an Anthroposophist, but his counterattacks destroyed forever two elements in my own

thought. In the first place he made short work of what I have called my "chronological snobbery," the uncritical

acceptance of the intellectual climate common to our own age and the assumption that whatever has gone out of

date is on that account discredited. You must find why it went out of date. Was it ever refuted (and if so by

whom, where, and how conclusively) or did it merely die away as fashions do? If the latter, this tells us

nothing about its truth or falsehood. From seeing this, one passes to the realization that our own age is also

"a period," and certainly has, like all periods, its own characteristic illusions. They are likeliest to lurk in

those widespread assumptions which are so ingrained in the age that no one dares to attack or feels it necessary

to defend them.

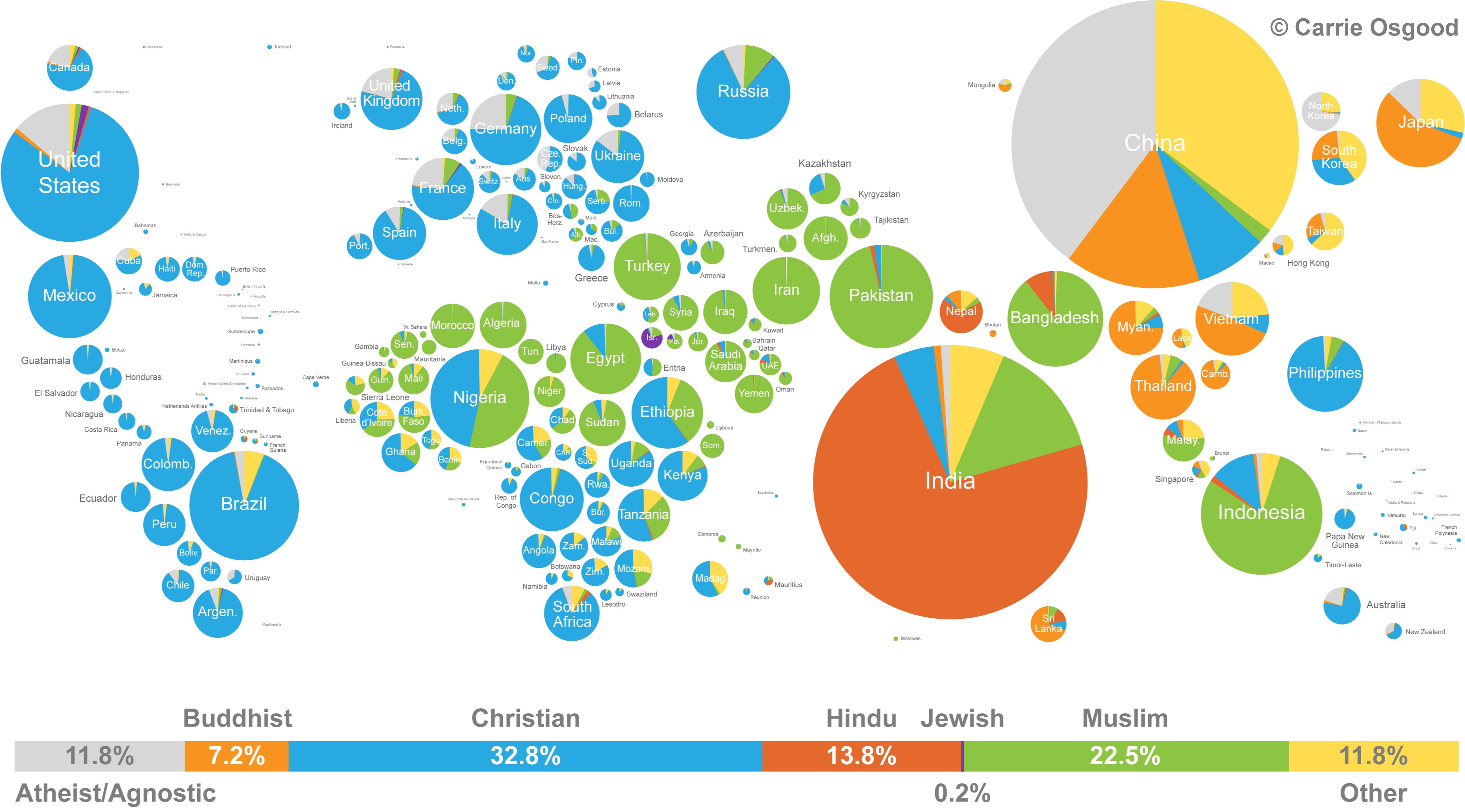

According to a survey published by the Encyclopedia Britannica, 2% of the world's population identifies as atheist, a global change of -0.17% from 2000 to 2010. Whereas, the percentage of atheists in 1970 was 4.5%. A 2002 survey by Adherents.com estimates the proportion of the world's people who are "secular, non-religious, agnostics and atheists" at about 14%.

Atheism is clearly the minority view, by a long way. But, before we become too confident in the West's self-perceived enlightenment, and remain sure that it is only a matter of time before the rest of the world will be educated and catch up with us, remember we've already had to recognise chronological snobbery as misguided, so let's not fall into the trap of geographical snobbery.

Of the global atheists and non-religious, 75% reside in Asia and the Pacific, mostly in China - a Communist state that actively discourages religion (or support for any group other than the governing party) - and Japan, while 12% reside in Europe and 5% in North America.

A study on global religiosity, secularity, and well-being notes that it is unlikely that most atheists and agnostics base their decision to not believe in gods on a careful, rational analysis of the pertinent philosophical and scientific arguments...Europeans score about as poorly on tests of scientific knowledge as do the more religious American population. It seems for both theists and atheists, belief largely depends on the culture of where you live.

It seems, to my mind at least, that we cannot dismiss the beliefs of the past simply because they are of the past, until we have proven them to be wrong. Similarly, we cannot dismiss the beliefs of the rest of the world. In fact, whether theist or atheist, we must analyze our context to understand its impact on our beliefs.

By all means doubt, but we must know why we doubt. We must have refuted the arguments, either for or against God, with an open mind and to our own satisfaction. Crucially, we must not believe either way simply because everyone else we know, or see in the media, thinks that way.

Know that despite what we may see in the media, religious people are not just the ill-educated, red-faced fanatics: they are anyone from physicists to philosophers, from the stubborn to the reasonable, the resolute to the open-minded, and indeed the red-faced fanatics to the calm and caring. But, given the variety of religious people, how is it that religous people are often thought of as simple-minded, or that they believe in religion in spite of science?

Personally, I have noticed that most stories in the mainstream media try to represent a certain narrative and generally religion tends to suffer a negative narrative.

A quick look at the media outlets during election time - or at any time, but it's most obvious during elections - tells us that often what they present is little more than attention-grabbing headlines, intended to do nothing more than generate revenue and further the interests of the owners. If religion became fashionable tomorrow, or even if the media moguls so desired, they would be publishing stories in full support of all things religious, and questioning how anyone could ever be so blind as to be an atheist.

It currently seems to be fashionable, at least in the "Western world", to scoff at religion and to instead claim to be a person of science, with an air of enlightened intelligence. For a listener, who has at least a little knowledge of religion, it often betrays the speaker to be someone who will espouse claims without the slightest research, or any real knowledge of a subject, and as such of a lower wordliness than they wish to portray. Often, atheism appears to be a trend, propogated by those who wish to be perceived as wordly and knowledgable.

There are a few famous atheists, currently doing well in the media today, who profess atheism to be the only sensible conclusion. Richard Dawkins is an example of such a person. He is, undoubtedly, a very clever scientist, or more precisely, biologist, who can often be seen persuading his audience to his way of thinking with the greatest of ease - maybe because their audience knows to whom they are about to listen and are already converted, but it cannot be denied that Dawkins is a good orator and clever.

However, before you take a famous atheist's word for it, on the assumption that they are clever and successful, and so are probably correct, consider their credentials, as the Professor of English Literature at Lancaster University, Terry Eagleton, did in his review of Dawkins' book, "The God Delusion":

Imagine someone holding forth on biology whose only knowledge of the subject is the Book of British Birds, and

you have a rough idea of what it feels like to read Richard Dawkins on theology. Card-carrying rationalists like

Dawkins, who is the nearest thing to a professional atheist we have had since Bertrand Russell, are in one sense

the least well-equipped to understand what they castigate, since they don't believe there is anything there to

be understood, or at least anything worth understanding. This is why they invariably come up with vulgar

caricatures of religious faith that would make a first-year theology student wince. The more they detest

religion, the more ill-informed their criticisms of it tend to be. If they were asked to pass judgment on

phenomenology or the geopolitics of South Asia, they would no doubt bone up on the question as assiduously as

they could. When it comes to theology, however, any shoddy old travesty will pass muster...What, one wonders,

are Dawkins's views on the epistemological differences between Aquinas and Duns Scotus? Has he read Eriugena on

subjectivity, Rahner on grace or Moltmann on hope? Has he even heard of them? Or does he imagine like a

bumptious young barrister that you can defeat the opposition while being complacently ignorant of its toughest

case? Dawkins, it appears, has sometimes been told by theologians that he sets up straw men only to bowl them

over, a charge he rebuts in this book; but if 'The God Delusion' is anything to go by, they are absolutely

right.

So, if we are to come to a conclusion either way, it is up to us to both consider our sources and their credentials, and to ignore the opinion of the day, as it is given to us by the media, and form our own, considered opinions from either the unbiased, or the equally biased opposites, and therein find our truth.

And we must do it with an open mind. We must also be careful not to fall into the trap of being un-scientific, as highlighted by Rev. Celestine Kapsner:

For a time it was fashionable to scoff at demoniacal possession as part and parcel of an outmoded superstition

of bygone ages of ignorance — like the attitude of a lifetime ago in regard to the miracles of Lourdes. But

facts are stubborn, also against the scoffing of so-called enlightened criticism. Stubborn facts cannot be

denied even when they baffle all natural explanation. The absurd thing about such a position is that the critics

"just know" that supernatural or preternatural phenomena simply "cannot be".

We have become much more sober in our day. And it is a healthy sign that the man of education no longer scoffs

so readily at that which he cannot explain. So much has been gained for perennial common sense.

While you might not agree with what Rev. Kapsner believes, he makes the important point: we cannot accuse those that believe in God of being un-scientific by using arguments such as, "the supernatural simply cannot be" (that would be the height of irony).

When making our decision, we must not fall foul of fashion. If you care enough to make a decision, have the courage to make the decision you believe to be correct, and make sure you do it based on the facts as you understand them, not as popular media present them.

But, should we care enough to make a decision?

We might consider the chance of an afterlife to be very small, and so the risk of ending up in the wrong place for all eternity to be so small it is negligable. But, given even the smallest possibility that there is indeed an eternal afterlife, the outcome could be so severe that we should spend at least some time conducting even a small amount of open-minded research.