As we discovered in the previous chapter, "science", e.g. logic, mathematics, cosmology, geology, physics, chemistry, biology, psychology, sociology, anthropology, etc, creates maps to understand and predict the behaviour of the reality they are studying, which are often in the form of mathematical equations, but often mathematics is an inappropriate language to describe the theories, such as in the field of psychology.

History also creates maps, obviously not using mathematical equations, but by analysing historical sources by considering their context and the biases with which they were recorded, to gain as true a picture as possible of the reality they are trying to understand.

Theology is the "ology", or the field of study, of understanding God. Obviously, it is less similar to the natural sciences, where we create mathematical equations to predict the behaviour of what we are studying and repeat experiments in a controlled environment to prove our equations (our maps) are accurate. We cannot make a hypothesis, put God in a controlled environment and ask him to perform the same miracles numerous times over, so we can say we have enough samples to be able to confirm that it is statistically likely our hypothesis is correct and that God could have performed the miracle in question, any more than a psychologist could make a hypothesis about how another person will behave and ask them to perform a task 1000 times over - they may not want to do it.

Theological maps are more similar to those created in the field of History. They analyse contemporary and historical sources, by considering their context and reliability, to try to understand God - they collate the evidence for God to try and gain as full an understanding as possible.

A Christian's main map for understanding God is, as you might expect, the bible. The part of the bible that makes Christianity Christianity is the New Testament, which is a collection of 27 short Greek writings, commonly called books, the first 4 of which are historical in character and mainly record Jesus' 3 short years of active ministry, for different audiences, as written by Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. The fifth book is a continuation of the third, but gives us an account of the rise of Christianity after Christ's resurrection and ascension into heaven, and the spread of Christianity in a westerly direction, from Palestine to Rome, through the acts of the apostles, within 30 years of Jesus' crucifixion in Jerusalem.

Christians also have the Old Testament - the revelation of God to the Jewish people up to the time of Jesus. But, as Jesus came to reveal God more fully to the Jewish people and to the rest of the world, the map we will concentrate on here is the New Testament.

If we are to use the New Testament to understand God, or indeed to understand whether the idea of God is even plausible, we must first understand how accurate it is. Given that the New Testament is historical in nature, accuracy depends on whether the authors knew what they were recording, or if they just recorded hearsay and rumours many years after the events.

Historians have a number of tools they could use when assessing the credibility of ancient documents - it is these tools that we must use to objectively assess the credibility of the New Testament accounts of what Jesus said and did.

In assessing trustworthiness of ancient historical writings, one of the most important questions is: how soon after the events took place were they recorded? In other words, if, as one of my friends liked to repeat: the bible was written hundreds of years after Jesus lived by people who never even knew him!

is true, our records of Jesus, and hence our (Christians') understanding of God, could be based on shaky ground. So, the first question we must answer is, when was Jesus publicly active?

Jesus' Ministry

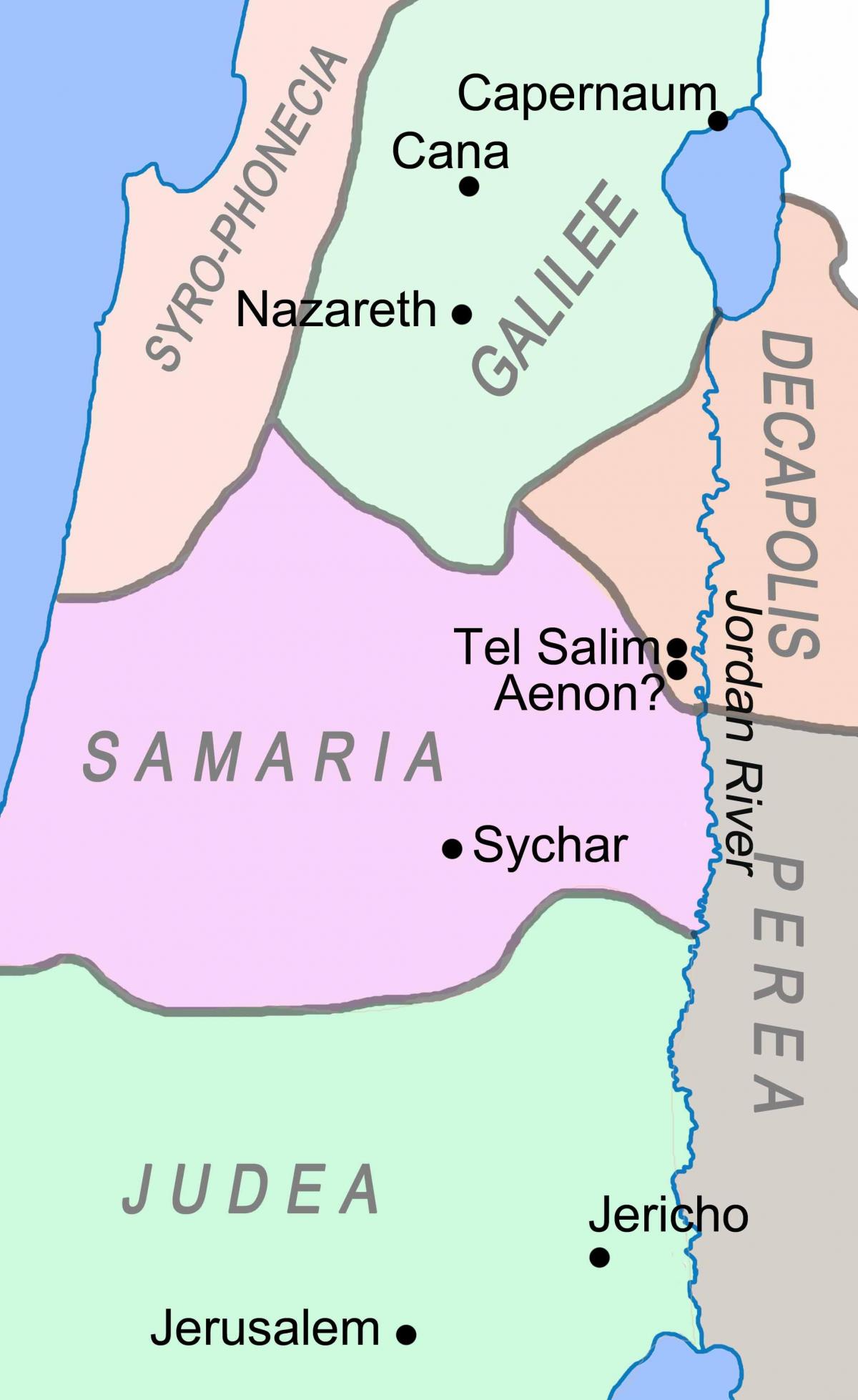

It is generally agreed that the crucifixion of Jesus took place about AD 30. According to Luke 3:1, the activity of John the Baptist, which immediately preceded the commencement of Jesus' public ministry, is dated in the fifteenth year of Tiberius Caesar

. Tiberius became emperor in August, AD 14, and according to the method of computation current in Syria, which Luke would have followed, his fifteenth year commenced in September or October, AD 27 .

John's Gospel mentions three Passovers after this time; the third from that date would be the Passover of AD 30, at which it is probable that the crucifixion took place. At this time, we also know from other sources that Pilate was the Roman governor of Judea, Herod Antipas was tetrarch of Galilee, and Caiaphas was Jewish high priest - all of whom are mentioned in their respective offices at the time of Jesus' crucifixion, by the New Testament accounts.

So, Jesus' public ministry - his teaching and the miracles he reportedly performed - lasted from AD 27 to AD 30.

The Recording of Jesus' Ministry

The majority of modern scholars fix the dates of the four Gospels as:

- Matthew, c. 85-90 AD

- Mark, c. 65 AD

- Luke, c. 80-85 AD

- John, c. 90-100 AD

Whichever dates we settle on, we can be confident that the time between the actions and teachings of Jesus and the writing of the New Testament books was short enough to satisfy historical credibility; many who could remember what Jesus said and did, both believer and ardent sceptic, would have still been alive when they were written, and as such able to provide first hand testimony and refute false claims.

Although the original books of the New Testament were written sufficiently close to the events they recorded to be considered reliable, another point is often made: Even so, we don't have a copy of the original manuscripts, so they were probably exaggerated or lost in translation

, or similarly: Jesus was just a really great moral teacher, and the miracle stories came about through exaggerations

. It's a point that needs addressing.

While we may be confident the first records were an accurate account of the events of Jesus' ministry, can we be confident our copies are an accurate replica of the first records? Or, are they exaggerations?

Manuscript Attestation

Manuscript Attestation is a technique used by historians to understand the reliability of a historical document, by examining how many copies of the document we have now and how close in time to the original document those copies were made.

Let's compare the New Testament writings to other ancient manuscripts that we rely upon:

Not many copies of ancient manuscripts remain today. Historians rely on copies of a small number of works that did survive to inform us of life and events of the time. Such well-known works are: the works of the Greek historians Herodotus and Thucydides, the work of the Roman senator and historian Tacitus, Caesar's Gallic war, and Livy's Roman History.

The earliest copies we have of the works of the Herodotus and Thucydides, who wrote in the 5th century BC, are from AD 900, and we only have eight copies. There is a 1000 year gap between the original work of Tacitus, who wrote in the 2nd century AD, and our first copies of his work, of which we only have 20. Only 9-10 copies of the record of Caesar's Gallic war in the 1st century BC exist, and the first copies we have were created 950 years after the original work. There is a 900 year gap between Livy's Roman History, which he started in the 1st century BC, and our first copies, of which there are only 20. Compare this to the copies of the New Testament, which was written between 40 and 100 AD and we see we have manuscript attestation that far surpasses work of a similar time: we have partial copies from 130 AD and full copies by 350 AD - a gap of only 90 to 250 years - and we have more than 5300 Greek copies, 10,000 Latin translations and 9300 other translations.

Or, to put it another way:

It becomes clear that the reliability of the New Testament writings is so much greater than the evidence for many writings of classical authors, the authenticity of which no one dreams of questioning. If the New Testament were a collection of secular writings, their authenticity, integrity and accuracy would universally be regarded as beyond all doubt.

From the viewpoint of the historian, the same standards must be applied to both secular and religious writings. However, it is understandable that people lay a greater burden of proof on the New Testament writings, given that the character and works of its chief Figure are so unparalleled, and their message is so life-changing for every single person on earth - we want to be as sure of their truth as possible. Fortunately, there is actually much more evidence for the New Testament writings than there is for other ancient writings of a comparable date.

Furthermore, in addition to full copies of the New Testament manuscripts, there are allusions to and quotations from the New Testament books, written between AD 90 and 160 by the leaders of the early Church, which shows their familiarity with most of the books of the New Testament. Throughout the second century, similar familiarity is evidenced through further writings, which recognise the authority of the New Testament. This reinforces the evidence for the early dates of the original documents and the unparalleled reliability of the copies we have, according to manuscript attestation.

Textual Criticism

A field related to Manuscript Attestation is Textual Criticism. Textual Criticism attempts to determine, as exactly as possible, the original words of a document in question.

It can be proved easily by experiment that it is difficult to copy out a passage of any considerable length, without making one or two mistakes at least. When we have documents like the New Testament, which have been copied and recopied thousands of times, the scope for copyists' errors increases enormously. However, as the number of errors increases with the number of copies, the means of correcting such errors increases proportionately to the number of copies, because it is unlikely that each scribe made exactly the same error in exactly the same place. So, due to the huge number of copies of the New Testament, the margin of doubt in recovering the exact wording of the original documents is remarkably small - that is to say, our confidence that we have the original wording of the New Testament documents is very high indeed.

From an historian's perspective, any doubt which remains within textual criticism of the New Testament is so limited that it does not affect the historical truth nor Christian faith or practice. Sir Frederic Kenyon, a highly respected biblical and classical scholar, makes a good summary when he says:

The interval then between the dates of original composition and the earliest extant evidence becomes so small as to be in fact negligible, and the last foundation of any doubt that the scriptures have come down to us substantially as they were written has now been removed. Both the authenticity and the general integrity of the books of the New Testament may be regarded as finally established.

In other words, we have today a reliable copy of the original New Testament documents.

Yeah, but, they were probably written by a bunch of people looking to control the masses

sounds more like a conspiracy theory than a genuinely held belief - particularly given that the authorites at the time were the Roman Empire, which tried its best to stamp out early Christianity through brutal persecution, and the Jewish authorities, which also tried its best to eradicate what it saw as a heretical new sect - but it is something that has been put to me in the past, so let's investigate it nonetheless.

We now know that we have an accurate copy of the first records, but if the records were created by untrustworthy authors, we could not trust them to be an accurate reflection of reality, and accordingly, they would be of little use to us today. For the map to be of any help to us in understanding God, or even the possibility that God exists, we must be sure we can trust its authors.

There are lots of philosophical arguments one could make in trying to prove or disprove the validity of the New Testament books. For example, in my opinion, it would not seem likely to try and base a movement on someone with Jesus' background. Throughout ancient history, and even in modern times, it has been the rich who make the headlines, and the rich and famous who people follow - even ancient myths featured the rich. For Jesus, the son of a carpenter from a backwater town to be written about is unprecedented and, as such, was the source of much reluctance to believe in Jesus and to follow him even at the time. But my opinion aside, let's look at the evidence we have.

The historian's tool, Source Criticism, tries to get behind the documents, to help us understand all we can about the source. Source Criticism is more speculative in nature than Manuscript Attestation and Textual Criticism, but it is nevertheless an important area of study: the more we understand about the source - in this case the four authors of the four Gospels - the more able we are to interpret their motives and evaluate their trustworthiness.

The four Gospels fall naturally into two groups: Matthew, Mark and Luke on one side, in a group called the Synoptic Gospels, and John on the other. We'll have a look at the authors of the Synoptic Gospels first.

The Synoptic Gospels

The Synoptic Gospels are so called because they provide a similar synopsis (a similar summary) which allows them to be studied together. But more than that, the Synoptics agree closely in words, arrangement of sentences and other details. The substance of 606 out of 661 verses of Mark appear in Matthew, and 350 verses of Mark appear in Luke, with little change. Or, to put it another way, of the 1068 verses of Matthew, about 500 contain material also found in Mark, and of the 1149 verses in Luke, about 350 are paralleled in Mark. There are only 31 verses in Mark which have no parallel in either Matthew of Luke. When we compare Matthew and Luke, we find these two have about 250 verses containing common material not paralleled in Mark. This common material is cast in language which is sometimes practically identical in Matthew and Luke, and sometimes shows considerable divergence. We are left with about 300 verses in Matthew whose substance is particular to that Gospel, and about 550 verses unique to Luke.

Or, to put it another way:

Why Were the Synoptic Gospels So Similar?

Oral Theory

One theory put forward to explain the similarities is the "Oral Theory", which states the narrative teaching of the apostles was handed on by word of mouth in a very systematic manner. It is doubtless that oral tradition did exist, and it existed alongside the written Gospels. While it would easily explain how unusual words and expressions would appear in all the Synoptics, it seems a less likely explanation for the similarities in language (such as parenthesis like this, for example), unless the spoken teachings were learnt so exactly that they became practically the same thing as the written Gospel. For this reason, the Oral Theory fell out of favour.

Document Theory

The Documentary Theory given most credence is that the source for the common portions of the Synoptics is the oral preaching of Jesus' disciple, St. Peter, translated from Aramaic into Greek, by Mark. That is to say, the Gospel of Mark is the source for the common parts of Matthew and Luke. It is proposed that the differences in Matthew and Luke, compared to Mark, come from the fact that Matthew and Luke felt perfectly free to alter their sources and narrative events differently, as seemed best to them. After all, they each had other sources besides Mark, including other eyewitnesses. It is further postulated that the areas common to Matthew and Luke, but not Mark must come from another early document - commonly referred to as 'Q'. It is clear that Matthew and Luke had other sources, as did Mark, as their Gospels each have substance unique to them.

Form Criticism

In the early 1900s, the Oral Theory re-appeared in a different form, known as Form Criticism. Form Criticism aims at recovering the oral forms, or patterns, in which the original teachings were cast, even before circulation of such documentary sources as may lay behind the Gospels. One of the results of Form Criticism is the recognition that the Documentary Theory by itself is as inadequate to explain all the facts, as was oral theory in its previously mentioned form.

Another important recognition of Form Criticism was of the universal tendency in ancient times to stereotype the forms in which religious preaching and teaching were cast. In the days of the apostles, there was a largely stereotyped preaching of the deeds and words of Jesus, originally in Aramaic, but soon in Greek as well. It is this oral tradition that lies behind the Synoptic Gospels and their documentary sources.

Telling a story in a stereotyped form is rarely entertaining, but there are times, even today, when a stereotyped form is relied upon. Consider a police officer recounting the events of a crime: they would not decorate their description with oratory flair, instead they stick closely to the facts in language commonly used to describe such events. What they lose in flamboyance, they gain in accuracy, ease of retention and ease of understanding. In this style, the words and deeds of Jesus would have been communicated orally.

Perhaps the most important conclusion of Form Criticism is that through recovering the oral forms that informed the Gospels - whether directly or through an intermediate document - we find that no matter how far back we go to the roots of the Gospel, we never encounter a non-supernatural Jesus. In other words, the written accounts of Jesus' activity are faithful to the oral retelling and eyewitness accounts.

Who were the Synoptic Evangelists?

Although the Synoptic Gospels have common sources - whether they were written, or oral, or both - it is clear they also have independent sources. The Synoptic Gospels were written by different authors for different reasons and audiences. The historian's tool, Source Criticism, can be used to try to understand the documents' authors and their intentions for putting pen to paper.

Mark - c. 65 AD

Mark's Sources

Papias, the bishop of Hierapolis in Asia Minor, gathered information on the origin of the Gospels from Christians of an earlier generation than his own, people who had conversed with Jesus' apostles first-hand. About AD 130-140, Papias documented his research in, An Exposition of the Oracles of the Lord. In this work, he writes: Mark, having been the interpreter of Peter, wrote down accurately all that he [Peter] mentioned, whether sayings or doings of Christ; not however, in order. For he was neither a hearer nor companion of the Lord; but afterwards, as I said, he accompanied Peter, who adapted his teachings as necessity required, not as though he were making a compilation of the sayings of the Lord. So then Mark made no mistake, writing down in this way some things as he [Peter] mentioned to them; for he paid attention to this one thing, not to omit anything he had heard, nor to include any false statement among them.

Luke's Acts 10:36-41 transcribes the preaching Peter made to a gathering in the house of a believer, the Roman centurion Cornelius, where Peter summarizes Jesus' ministry: Jesus' baptism by John; Jesus' miracles, showing his authority was from God; Jesus' journey to Jerusalem; Jesus' crucifixion; Jesus' resurrection from the dead and appearance to many people. This outline of Jesus' ministry, as preached by Peter, follows the same structure as Mark's Gospel, which further reinforces the findings of Papias.

Peter was the first disciple to be called, at the start of Jesus' Galilean ministry, and one of his most trusted. He was with Jesus to the end, and is noted as the chief preacher of the Gospel among the disciples, in Luke's Acts (after the crucifixion of Jesus). Therefore, the original oral theory was not far wrong, as in translating Peter's oral teachings, Mark's work largely became the oral preaching written down.

There is also a tradition that it was in Mark's parents' house that the Last Supper was held and it is probable that Mark was the young man who followed Jesus and his disciples to the garden, Gethsemane, where they prayed after the Last Supper (and who was only wearing a linen cloth, which he lost during his narrow escape when they arrested Jesus and the disciples fled). It is likely, therefore, that Mark included some of his own memories of Jesus' trial and crucifixion along with Peter's teaching.

Mark's Audience

Mark wrote his book to communicate the words and works of Jesus to the Christian community in Rome. His Gospel is the shortest of all the Gospels, which would have suited the simple, straightforward approach the Romans favoured. In his work, Mark gives reference to the Old Testament only once, again this would have suited his readership, knowing that they had little or no knowledge of the Old Testament. Although the originally intended readership was Rome, his Gospel was soon widely circulated throughout the Church.

Matthew - c. 85-90 AD / shortly after 70 AD

Matthew's Sources

Again, Papias provides insight into the origins of the Gospels, this time Matthew's, when he says: Matthew compiled the Logia in the 'Hebrew' speech, and everyone translated them as best he could.

The New Testament writers usually refer to the language Aramaic as Hebrew, and so provide no distinction between the two closely related languages. It is likely that Matthew's Logia were written in Aramaic, as this was the common language of Palestine at the time, and probably the language in which Jesus and his disciples spoke. Various suggestions have been made as to the meaning of the term Logia - the literal meaning is "oracles" - but the most probable is that it refers to a collection of Jesus' sayings.

Matthew: the Author of the Q-Gospel

The material common to Matthew and Luke, but not from Mark, commonly referred to as the 'Q' Source, largely consists of the sayings of Jesus. When the Q material is isolated, by comparing Matthew and Luke, it reveals a work constructed along the lines of one of the prophetical books of the Old Testament - Jesus was recognised as a great prophet by his contemporaries. These books commonly contain an account of the prophet's call to his ministry, with a record of his sayings set in a narrative framework, but no mention of the prophet's death. The reconstructed Q material follows this pattern by beginning with Jesus' baptism by John and his temptation in the wilderness, which formed the prelude to his Galilean ministry, followed by groups of his sayings set in a minimum of narrative framework, but does not describe the Passion(suffering and crucifixion) of Jesus.

It seems likely that the Logia Papias spoke of is the same document as the Q material. Papias' statement that the Logia were compiled "in the 'Hebrew' speech" accords with the internal evidence that an Aramaic substratum underlies the Q material in Matthew and Luke. His statement "everyone translated them as best he could", suggests several Greek versions of the Logia existed. The existence of multiple, slightly differing translations explains some of the differences in the sayings of Jesus in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, as in many places where the Greek of these Gospels differs, it can be shown that one and the same Aramaic original underlies the variant Greek translations. Furthermore, when the sayings of the Q material are turned into Aramaic, they are shown to exhibit regular poetical rhythm. Teaching that follows a recognizable pattern is more easily memorized, hence prophets taught in poetical form. Where this form is preserved, we have further assurance that Jesus' teaching has been handed down to us as it was originally spoken.

Matthew's Audience

The Gospel of Matthew appeared in the neighbourhood of Syrian Antioch some time after AD 70. It represents the substance of the apostles' preaching, as recorded by Mark, expanded by the incorporation of other narrative material, and combined with a Greek version of the Matthean Logia together with sayings of Jesus derived from other sources. Matthew's Gospel has been arranged to be a manual for teaching and administration within the Church. The sayings of Jesus are arranged to deal with five great discourses: the law of the kingdom of God (chapters 5 - 7); the preaching of the kingdom (10:5-42); the growth of the kingdom (13:3-52); the fellowship of the kingdom (18); and the consummation of the kingdom (24-25). The narrative of Jesus' ministry is arranged such that each section leads on naturally to the discourse that follows it. The book is prefaced by a prologue describing the nativity (1-2) and concluded by an epilogue relating to passion and ultimate victory of Jesus (26-28).

Matthew's Gospel was written primarily for a Jewish Christian audience, which is why he references Old Testament more than the others and makes an effort to highlight the fulfilment of the Old Testament in Jesus.

Luke - c. 80-85 AD / shortly before 70 AD

Luke's Audience

Luke, the writer of the third Gospel and Acts of the Apostles is the only Gentile (non-Jewish) of the Gospel writers. He addresses his work to an otherwise unknown person, Theophilus, who seemingly had some knowledge of Christianity and appears to have had an official status, as Luke addresses him, "most excellent" - the same title the apostle Paul uses when addressing Felix and Festus, the Roman governors of Judea. Luke himself explains the purpose of his work:

Most excellent Theophilus! Since many have undertaken to draw up a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us, as they have been transmitted to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the Word, I too, having followed the whole course of events accurately from the first, have decided to write an orderly account for you, in order that you may be sure of the reliability of the information which you have received.

Luke, a physician from Antioch in Syria, who had inherited the traditions of Greek historical writing, set out to inform his readership of the origins and development of Christianity, as accurately as possible, through diligent research of multiple sources, including Mark's Gospel, Matthew's Logia and his own eyewitness account of some of the events he recorded.

Luke: the Accurate Historian

Luke is the only New Testament writer who mentions the names of Roman Emperors, as well as a great many number of other high-ranking officials, in order to accurately date the events he records - as was the tradition of Greek historical writing. For example, Luke writes: In the fifteenth year of the reign of Emperor Tiberius, when Pontius Pilate was governor of Judea, and Herod was ruler of Galilee, and his brother Philip ruler of the region of Ituraea and Trachonitis, and Lysanias ruler of Abilene, during the high priesthood of Annas and Caiaphas, the word of God came to John son of Zechariah in the wilderness.

Such complex synchronization to place his Gospel in the wider context of world history is a risk, as any mistake would allow his critics to label him inaccurate. However, Luke passes the test admirably throughout his work.

One of the events to which Luke was an eyewitness is Paul's voyage from Palestine to Italy, including the shipwreck at Malta. The story recorded by Luke has been hailed as "one of the most instructive documents for ancient seamanship". The experienced yachtsman, James Smith, was well acquainted with the part of the Mediterranean over which Paul's ship sailed, and in his 1848 work, The Voyage and Shipwreck of St. Paul, he attests to the remarkable accuracy of Luke's account of each stage of the voyage, and he was able to fix, by the details given by Luke, the exact spot on the coast of Malta where the shipwreck must have taken place, 2000 years earlier.

Such accuracy, as displayed by Luke, cannot be accidental and cannot simply be turned on at a whim: it is a habit of mind. In our day to day experience, we know people who are habitually, even insufferably, accurate, just as we know people who can be depended on to be inaccurate. Luckily for those who wish to study early Christianity, Luke is proven time and again to be the former, by archaeologists and historians alike.

Luke's Sources

The first Gentile church was in Antioch in Syria, so Luke, being from the same place, would have had the opportunity to learn from its founders. He may have even met Jesus' first disciple, Peter, who once paid a visit there. While that is speculation, it is certain that Luke would have learnt a lot from Paul - although Paul was not a follower of Jesus before the crucifixion, Paul learnt all he could about Jesus from the disciples, including Peter, after his Damascene conversion, and Paul was instrumental in establishing and guiding many of the first churches. Luke spent two years in or near Palestine during Paul's last visit to Jerusalem and detention in Caesarea, where he had great opportunities to increase his knowledge of Jesus and the early Church. While in Palestine, he is known to have met James, Jesus' step-brother (or cousin - the original word is ambiguous), at least once. Some of Luke's unique material reflects the oral Aramaic tradition, which Luke received from various Palestinian informants, while other parts were evidently derived from Christian Hellenists. On the arrival of Paul and Luke in Caesarea, they stayed the house of Philip the Evangelist, and it is likely much of Luke's information was derived from Philip and his family.

After Paul's two-year detention in Caesarea, he exercised his right as a Roman citizen to appeal his case to Caesar, and so he was taken, under guard, to Rome, and Luke went with him - it was on this voyage that they were shipwrecked in Malta. While in Rome, about the year 60, Luke met the first Gospel writer, Mark. It is likely thanks to this encounter that Luke was able to include Mark's work in his own.

Literary criticism of Luke's Gospel suggests Luke first enlarged his version of the Matthean Logia by adding the information he acquired from various sources, especially while in Palestine, then he inserted at appropriate points blocks of material derived from Mark, especially where Mark's work did not overlap the material already collected, thus producing the third Gospel. The number of first-hand witnesses Luke met allowed him to cross-reference and corroborate his sources, to aid in the creation of an accurate and chronologically ordered account of Jesus' ministry, his miracles and teaching, and the teaching and miracles of Jesus' disciples before and after the crucifixion.

The Fourth Gospel - John, c. 90-100 AD

The Synoptists may give us something more like the perfect photograph; St. John gives us the more perfect portrait

Who is John?

The author of the fourth Gospel is the only one of the four Evangelists who claims to be an eyewitness, although the author never specifically states who he is. In the final chapter of this Gospel, the resurrected Jesus appears to seven of his disciples, who had joined Peter (a fisherman by trade) on a fishing boat on the Sea of Tiberius. The seven disciples present were: Simon [who was called] Peter, Thomas called the Twin, Nathanael of Cana in Galilee, the sons of Zebedee [James and John], and two others of his disciples

. The closing verses of the chapter, which end back on the shore, credit the disciple whom Jesus loved

as the eyewitness and author of the evidence presented:

Peter turned and saw the disciple whom Jesus loved following them; he was the one who had reclined next to Jesus at the supper and had said, “Lord, who is it that is going to betray you?” When Peter saw him, he said to Jesus, “Lord, what about him?” Jesus said to him, “If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you? Follow me!” So the rumour spread in the community that this disciple would not die. Yet Jesus did not say to him that he would not die, but, “If it is my will that he remain until I come, what is that to you?

This is the disciple who is testifying to these things and has written them, and we know that his testimony is true. But there are also many other things that Jesus did; if every one of them were written down, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written

We don't know who the "we" are, presumably a group of his friends and disciples who were responsible for the editing and publication of his Gospel, but we do have a good idea who "disciple whom Jesus loved" is.

We know the "disciple whom Jesus loved" was one of the seven to whom Jesus appeared at the Sea of Tiberius. The "disciple whom Jesus loved" is specifically mentioned at three other times in the Gospel:

- as one of the company of the Last Supper (Jn. 13:23),

- as being present at the crucifixion (Jn. 19:26)

- as an eyewitness, with Peter, of Jesus' empty tomb (Jn. 20:2)

According to the Synoptic Gospels (Mk. 14:17, Mt. 26:20, Lk. 22:14), Jesus ate the Last Supper with the twelve apostles, and there is no suggestion that anyone else was present with them in the upper room. Given that the fourth Gospel states "[the disciple who Jesus loved] was the one who had reclined next to Jesus at the supper", we can conclude that he was one of the twelve. Of the twelve, there were three who were, on occasion, admitted to a more intimate fellowship with Jesus: Peter, James and John. We would naturally expect "the disciple who Jesus loved" to be one of these three. He was not Peter, as Peter is explicitly distinguished from him in Jn. 13:24, Jn. 20:2 and Jn. 21:20. The remaining two of the three are the sons of Zebedee, James and John (who were the second pair to be called to follow Jesus after Peter and his brother Andrew). James was martyred no later than AD 44, so it is unlikely that the rumour the disciple who Jesus loved would not die should spread. Therefore, we are left with John.

In support of this conclusion, it is noteworthy that John is not mentioned by name in the fourth Gospel, and that while the other Gospel writers refer to John the Baptist as John the Baptist, he is simply referred to as John in the fourth Gospel. It is natural that an author would take care to distinguish between two characters in a narrative who bear the same name, but they would be less compelled to distinguish a character from themself. It is evidently not sloppiness that leads to the author of the fourth Gospel not distinguishing John the Baptist from John the disciple, as he is careful to distinguish between Judas Iscariot from Judas 'not Iscariot'. It is significant, therefore, that the author does not distinguish between John the Baptist and John the disciple, as he would certainly have known of him.

Alternative Theories

There have been challenges to the theory that John, son of Zebedee, wrote the fourth Gospel, due to discrepancies with the Synoptic Gospels. It is not up to me to state unequivocally one way or the other - I'm not qualified - but the rebuttals to the claims have lead me, personally, to be satsfied that they got it right when they ascribed John's name to the fourth Gospel.

One argument against Johannine authorship is that John was a fisherman, and thus illiterate and incapable of creating a work of such profound thought. It is true that fishermen in those times would generally have been illiterate, and more than that, they would have been among the least refined people in society - even today, we might prejudge those with physically demanding, labourer-type jobs, such as builders, plumbers, binmen, etc, to be incapable of scholarly, refined works, writing off such people as simply boorish. Indeed, thanks to their forthright nature, Jesus gave John and his brother the nickname, sons of thunder

. However, we should remember that John was likely a young man when he was a disciple of Jesus, and so he had decades in which to learn and develop.

Challenges worth a more in-depth analysis are the seeming divergences between John and the Synoptics, in terms of geography, chronology and diction.

Geographical Divergence Between John and the Synoptics

The main geographical divergence is that the Synoptists tell almost exclusively of a Galilean ministry, whereas John places most of Jesus' activity in Jerusalem and the rest of Judea. While it might seem a significant discrepancy at first, we know that John's Gospel was written after all three Synoptic Gospels - not to mention the other documents recording Jesus' teaching and miracles that were circulating at the time - so he would have seen that Jesus' activity in Galilee was well recorded. In John 7:1, we see that he knew perfectly well of Jesus' ministry in Galilee, and he may have felt little need to repeat what was already well recorded - after all, he wasn't writing for posterity, but to convince his contemporaries that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God. Additionally, the Synoptists implicitly confirm John's account of a Jerusalem ministry - before Jesus' final visit there, as recorded by the Synoptists - as they show that Jesus is known by the owner of a donkey in a village near Jerusalem and Jesus is expected for the Passover by the owner of a room in Jerusalem.

Different Lengths of Jesus' Ministry Between John and the Synoptics

The Synoptic accounts and John's account have Jesus' public ministry lasting very different lengths of time - a potentially worrying discrepancy at first glance if John was indeed one of Jesus' disciples. However, this is easily resolved when you look at John and the Synoptics together. The Galilean ministry detailed by the Synoptic Gospels lasts about a year, whereas John takes us further back in time, to a southern ministry of Jesus, before the imprisonment of John the Baptist. The year of the Galilean ministry, recorded by the Synoptists, fits between Jn. 5 and 7, ending at the Feast of Tabernacles in Jn. 7:2.

The activity of Jesus in Judea before his Galilean ministry also sheds new light on the Synoptic Gospels. For example, it becomes much more understandable that the fishermen Peter and his brother Andrew, and James and his brother John, left their livelihoods to follow Jesus, when we learn from John that they met Jesus previously, while they were with John the Baptist in Jerusalem.

The activity of Jesus and his disciples after the Galilean ministry, according to the Synoptic Gospels, becomes more intelligible when it's placed in the context of John's timeline, where the Galilean ministry ended in the autumn of AD 29, that Jesus then went to Jerusalem for the Feast of Tabernacles, that he stayed there until the Feast of Dedication in December, then spent some months in retirement in the Jordan valley, before returning to Jerusalem about a week before the Passover of AD 30. John's record, by its recurring mention of festivals, provides a helpful chronological framework to the Synoptics, which is lacking in chronological indications for the period between Jesus' baptism and his last visit to Jerusalem.

Difference in Jesus' Diction Between John and the Synoptics

There are differences in the diction of Jesus between the fourth Gospel and the other three. Although some might say that this means it's unlikely that the disciple John wrote the fourth Gospel, because John the disciple was present at Jesus' teachings and so should have recorded the same style of speech as the Synoptics, actually, these differences in diction become perfectly understandable when we realise that in the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus was largely talking with the country people of Galilee, whereas in the fourth Gospel, Jesus disputes with the religious leaders of Jerusalem or talks intimately with his closest disciples.

The Missing Miracles

The final challenge is that of the miracles and other events in Jesus' ministry that are missing from John's Gospel. For instance, it is notable that the Synoptics record the miracles of Jesus' transfiguration, his healing of lepers and his teachings of the Sermon on the Mount, whereas they cannot be found in the Gospel of John. Given that John the disciple would likely have been present for these events, and is indeed recorded as being present by the Synoptic Gospels, the question arises, why would John the disciple not have recorded these momentous events?

The author of the Gospel himself gives us the answer when he says in his closing paragraph: This is the disciple who is testifying to these things and has written them, and we know that his testimony is true. But there are also many other things that Jesus did; if every one of them were written down, I suppose that the world itself could not contain the books that would be written

John's Gospel was written after the Synoptic Gospels were in circulation, not to mention other documents, as mentioned by Luke in his opening paragraph: Since many have undertaken to draw up a narrative of the things that have been accomplished among us

.

John's Audience

John states the purpose of his Gospel when he says, Now Jesus did many other signs in the presence of his disciples, which are not written in this book. But these are written so that you may come to believe that Jesus is the Messiah, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.

The material John selects is done so for the purpose of supporting that premise, and so he may have felt no need to repeat the Synoptic Gospels, given the wealth of material that was in circulation at the time - he wasn't to know that only four works describing Jesus' ministry would survive through the next 2000 years. John's Gospel supplements what was widely known at the time about Jesus, including miracles and events unique to John's Gospel, such as Jesus turning water into wine at the wedding at Cana, the raising of Lazarus from the dead, and Jesus' appearance on the lake to Peter and the six other disciples (including John himself).

Does Authorship Matter Anyway?

Whoever wrote the Gospel of John, the internal evidence bears witness to the fact that the author was an eyewitness to the events he recorded, by the level of circumstantial detail that exists in the retelling of Jesus' miracles. It is also clear that the author was a Palestinian, as his accurate knowledge of places and distances in Palestine appears spontaneously and naturally throughout his account, unlike that of someone who receives their information second hand or from infrequent visits. He evidently also knows Jerusalem very well, as he fixes the location of certain places in Jerusalem with the accuracy of someone who must have been acquainted with the city before its destruction in AD 70. The author was also clearly a Jew: he is intimately familiar with Jewish practices and customs; he refers to many of the Jewish feasts, and uses them to mark the times of the year at which events occurred; he is well acquainted with the Old Testament; and he is familiar with the superior attitude with which those who received rabbinical training looked down on those who had not.

John's accurate knowledge of Jewish customs and beliefs, and the internal evidence of his Gospel, suggests he not only witnessed the remarkable events he recorded, but he understood them. The testimony of the theologian, philosopher and statesman, Archbishop William Temple puts John's contribution rather succinctly:

The Synoptists may give us something more like the perfect photograph; St. John gives us the more perfect portrait...the mind of Jesus Himself was what the fourth Gospel disclosed, but...the disciples were at first unable to enter into this, partly because of its novelty, and partly because of the associations attaching to the terminology in which it was necessary that the Lord should express Himself. Let the Synoptists repeat for us as closely as they can the very words he spoke; but let St. John tune our ears to hear them.

So, Were the Authors of the Gospels Trustworthy?

We now understand who the authors of the Gospels were and their intentions for writing their accounts. We know their accounts aren't disinterested or impartial, but the authors all believed Jesus to be the Son of God. So, can their accounts be trusted?

A Definite Beginning

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI reminds us that Jesus' dates are fixed, a definite point in time, during his critique of Luke's Gospel, when he writes, [Luke] again offers a meticulously detailed chronology of that particular moment in history: the fifteenth year of the reign of the Emperor Tiberius. He adds the names of the Roman governor that year, the tetrarchs of Galilee, of Iturea and Trachonitis and of Abilene, as well as the high-priests (cf. Lk 3:1f.). It was not with the timelessness of myth that Jesus came to be born among us. He belongs to a time that can be precisely dated and a geographical area that is precisely defined.

Circumstantial Support

This view is further reinforced by the writings of various non-Jewish people, such as the Syrian Mara Bar-Serapion who writes some time after AD 73 to his son, saying What advantage did the Athenians gain from putting Socrates to death? Famine and plague came upon them as a judgement for their crime. What advantage did the men of Samos gain from burning Pythagoras? In a moment their land was covered with sand. What advantage did the Jews gain from executing their wise king? It was just after that that their kingdom was abolished.

Mara was clearly not a Christian, otherwise he would have mentioned that Jesus rose from the dead. His mentioning Jesus confirms Jesus lived and was well known, without any intention to promote Christianity.

Similarly, the great Roman historian Tacitus, who wrote the history of Rome under the emperors, writes how Nero, in order to quell rumours that he instigated the fire of AD 64 that ravaged Rome so he could gain glory by rebuilding the city, blames Christians for the disaster. Tacitus writes, Therefore, to scotch the rumour, Nero substituted as culprits, and punished with the utmost refinements of cruelty, a class of men, loathed for their vices, whom the crowd styled Christians. Christus, the founder of the name, had undergone the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, by sentence of the procurator Pontius Pilatus, and the pernicious superstition was checked for a moment, only to break out once more, not merely in Judaea, the home of the disease, but in the capital itself, where all things horrible or shameful in the world collect and find a home.

It is obvious that Tacitus is no friend of the Christians, but his and others' statements confirm that the person of Jesus and his followers were not myth, but a historical reality, as they write with no intention of promoting Christianity and often with a loathing for it.

Even within the New Testament accounts themselves, we find claims that would damage their credibility. The first person Jesus told he was the Messiah was a Samaritan woman - whose testimony brought many people to believe in Jesus; and the first person to learn that Jesus was resurrected (the most important news in the entire universe) was a woman, Mary Magdalene. In a culture where a woman's testimony was not recognised in court, unless it was a trivial matter, to choose women as the bearers of such important news would give people who did not want to believe it an easy get out. In other words, if the Gospel writers were just making it up, they would have chosen men.

Direct Opposition

We know the authors of the Gospels were writing for different audiences, but they were all convinced Jesus was the Messiah. There were others, at the time of Jesus, who were convinced Jesus was not the Messiah - for example, the Jewish sect, the Pharisees, were utterly opposed to Jesus and his followers and were instrumental in contriving Jesus' crucifixion. The Pharisees are recorded, in Jewish law, to have said that Jesus was a transgressor who practised magic, led people astray, was hanged (crucified) on Passover eve, and his disciples healed the sick in his name. In another example of hostility towards Christianity, the Greek philosopher, Celsus, who was thoroughly opposed to Christianity wrote in his criticism of Christianity c. AD 175, that Jesus performed his miracles by sorcery

.

At no point, even from those most hostile to the claims of the Gospel, was it claimed that the events recorded in the Gospels did not occur. They claim either Jesus' miracles came from evil or that he simply fooled his followers, but they never disputed the events occurred.

Given we have an accurate record of the events that transpired around AD 30, it is up to us to form our individual opinions as to whether we believe Jesus was a charlatan or he is who he said he is. Or, in the words of Bono, Jesus was the Son of God or he was nuts

. Bono succinctly paraphrased what C.S. Lewis stated in more detail during a radio broadcast, when he said, I am trying here to prevent anyone saying the really foolish thing that people often say about him: 'I'm ready to accept Jesus as a great moral teacher, but I don't accept his claim to be God'. That is the one thing we must not say. A man who was merely a man and said the sort of things Jesus said would not be a great moral teacher. He would either be a lunatic — on the level with the man who says he is a poached egg — or else he would be the Devil of Hell. You must make your choice. Either this man was, and is, the Son of God, or else a madman or something worse. You can shut him up for a fool, you can spit at him and kill him as a demon or you can fall at his feet and call him Lord and God, but let us not come with any patronizing nonsense about his being a great human teacher. He has not left that open to us. He did not intend to. ... Now it seems to me obvious that he was neither a lunatic nor a fiend: and consequently, however strange or terrifying or unlikely it may seem, I have to accept the view that he was and is God

From Lewis' study, he came to the conclusion that Jesus is indeed who he said he is. When I made my conclusion, in addition to the reliability of the Gospels, I considered the people who Jesus had an effect on.

St. Paul

There has been no bigger change of heart, on any subject, than that of St. Paul's: his conversion on the road to Damascus still gives us today, 2000 years later, the saying "Damascene conversion". Paul, born Saul of Tarsus to Jewish parents in the city of Tarsus, Syria, around the same time Jesus was born, was a Jew and became a Pharisee a few years before Jesus' crucifixion (c. AD 30). It is possible that Paul was also a member of the Sanhedrin - the supreme Jewish court - and he described himself as the best Jew and best Pharisee of his generation: Paul had great zeal for adherence to the Jewish faith.

Saul the Persecutor

Paul, or Saul as he was still known, became a known terror to the early Christians. Although he never explicitly states his motivation for persecuting the new Jewish movement, we know that as a Pharisee at the time of Jesus' crucifixion, he was a member of the group which was instrumental in conspiring to have Jesus killed. He was opposed to the Christians' message that Jesus had been resurrected from the dead and is the Son of God - a hugely blasphemous claim in Saul's view - and it is likely that Saul believed that Jewish converts to the new Christian movement were not sufficiently observant of the Jewish law, and that Jewish converts mingled too freely with Gentile (non-Jewish) converts, thus associating themselves with idolatrous practices. So, Saul did everything he could to try and crush the Christian movement.

Saul appears to have overseen, or at least been present and approved of the stoning of the first Christian martyr, Stephen. Stephen was arrested by the Jews who disagreed with his preaching about Jesus and, because they could not win an argument against him, they accused him of blasphemy. He was then tried before the council, where his preaching enraged those present so much that they dragged him from the city and stoned him to death. From that day Saul led a severe persecution against the Christians, going from house to house, dragging off men and women and throwing them into prison. He subsequently obtained permission from the high priest to travel to the synagogues of Damascus and arrest any Christians he might find there and bring them back to Jerusalem as prisoners.

Paul the Promoter

It was on the road to Damascus where Saul becomes Paul. The gospel writer, Luke - who we know to be Paul's student - details the event in Acts: a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground and heard a voice saying to him, “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” he asked, “Who are you, Lord?” The reply came, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. But get up and enter the city, and you will be told what you are to do.” The men who were travelling with him stood speechless because they heard the voice but saw no one. Saul got up from the ground, and though his eyes were open, he could see nothing; so they led him by the hand and brought him into Damascus. For three days he was without sight, and neither ate nor drank.

Luke goes on to tell us of one of the disciples who was in Damascus, Ananias, was instructed by Jesus in a vision to go to meet Paul: So Ananias went and entered the house. He laid his hands on Saul and said, “Brother Saul, the Lord Jesus, who appeared to you on your way here, has sent me so that you may regain your sight and be filled with the Holy Spirit.” And immediately something like scales fell from his eyes, and his sight was restored. Then he got up and was baptised, and after taking some food, he regained his strength.

Even if we are initially sceptical of these supernatural events, what is undeniable is that Paul was converted from one of Christianity's greatest persecutors, to one of Christianity's chief promoters, subsequently travelling over 10,000 miles during the next thirty years to spread the message of Christianity to the Gentiles. These remarkable events were directly contradictory to Paul's zealously held world view, which did not allow for a dead and resurrected Messiah, but rather than try to rationalize them away, so he could hold onto the ideas he had studied in becoming a Pharisee, Paul decided the events he witnessed meant Christianity was true and that his fiercly held beliefs of a lifetime needed to change.

The Early Martyrs

St. Paul was not the only convinced Christian of the time. After Jesus' death, many Christians were imprisoned or murdered for their belief. A number of independent sources in antiquity attest to the disciples' willingness to suffer and even die for this belief. While this does not prove their beliefs were true, since people of other faiths are likewise willing to die for their convictions, being willing to die for their convictions does indicate that they believed they knew the truth. They believe they had seen the risen Jesus — and believed it strongly enough that they were willing to endure great suffering and even death for proclaiming it. Liars make poor martyrs. So we can establish that the original disciples not only claimed the risen Jesus had appeared to them, they really believed it.

The Unconvinced Witnesses

The Gospels tell us of whole towns in Judea and Galilee that were convinced to follow Jesus after they saw him heal people - not the unconvincing healing of back pain and other elusive ailments that charlatans even today "heal", but visible illnesses such as leprosy, blindness, epilepsy, withered limbs, and more, of all the people that were brought to him. However, there remained people who still would not follow Jesus' teaching. In Matthew 11:20-24, Jesus admonishes those who had seen his power, through miracles of healing, raising the dead and casting out demons, but who failed to repent their behaviour.

I have been lucky, as it is my natural inclination to behave as Jesus taught people how they should behave: putting others first and generally treating others how you wish to be treated. Or at least I recognise this as an ideal and I try to behave as such. Although I often fall short of the ideal, it is my goal, so it is much easier for me to accept Jesus' teaching and thus there is one less obstacle for me accepting Jesus for who he said he is. The Gospels give us examples of people who stood to lose their power and influence, or who simply didn't want to change their ways because they were enjoying their life too much, and so ignored the teachings of Jesus. One can have sympathy for these people, because letting that change in, even a little bit, would have turned their comfortable lives upside down, much as it would do for many today.

Matthew 9:34 tells us how the Pharisees, who stood to lose much influence by Jesus' teaching, rejected Jesus and his teaching, not by not recognizing powers, but by saying his powers came from evil. Even the Pharisees who would not accept Jesus, and stood to lose everything if everyone believed in Jesus, did not refute his claims on the grounds of trickery of falsehood, much less by claiming the events never happened.

I should be honest: I had heard sections of the Gospels read out every week in church, but until I researched for this website, I had never read them cover to cover. Reading the Gospels, now combined with knowledge of who wrote them and how accurate our copies are, revealed a Christianity that started from a definite place and in a definite time, and that grew rapidly to be a huge movement, due to the extraordinary miracles of Jesus and, by Jesus' power, those of his disciples.

As news of these events spread, the testimony of witnesses convinced many others that Jesus is the Son of God, and many people documented and translated these events. Even the most powerful of the worlds' leaders at the time were either convinced or troubled by this new movement, and they would be unlikely to waste their time on something that didn't have a sizeable following. The world had never before seen such a revolution and conversion, nor has it since.

Whichever side of the fence you come down on, as the scholar F. F. Bruce said, if you're going to have an opinion on the New Testament, you should read it.

This is what I did, and I learnt a lot more than I thought I would. If you are going to form an opinion on the claims of the Gospels, you should read them. Besides, it won't take long, as they were designed to get their message across to as many people as possible, and lengthy prose would be as likely to put as many people off reading and listening to that message 2000 years ago as it is today.